SciBase Journals

SciBase Dentistry and Oral Sciences

ISSN 2996-363X

- Article Type: Research Article

- Volume 2, Issue 1

- Received: Jan 19, 2024

- Accepted: Feb 27, 2024

- Published Online: Mar 05, 2024

Is There a Link Between the Increased Consumption of Sports Drinks and Dental Decay?

Peter Fine*; John Haughey

UCL Eastman Dental Institute, UK.

*Corresponding Author: Peter Fine

UCL Eastman Dental Institute, UK.

Email: p.fine@ucl.ac.uk

Abstract

Background: The role of oral health in influencing athletic performance has been well documented. The use of sports drinks has been linked with an increase in poor oral health including dental decay. The aim of this study was to investigate the possible association between sports drinks and dental decay/pain amongst elite athletes and the incidence of dental decay/pain.

Hypothesis: This study is looking at the hypothesis that the consumption of sports drinks leads to dental disease, particularly dental decay.

Level of evidence: Local and current random sample; randomized trial; cohort study or control arm of randomized trial; inception cohort study.

Methods: An opportunistic volunteer survey of elite athletes attending a varied international sporting competition.

Analysis of the data was undertaken using descriptive statistics, mean values and standard deviations. Associations between demographic information and results were presented. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

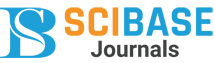

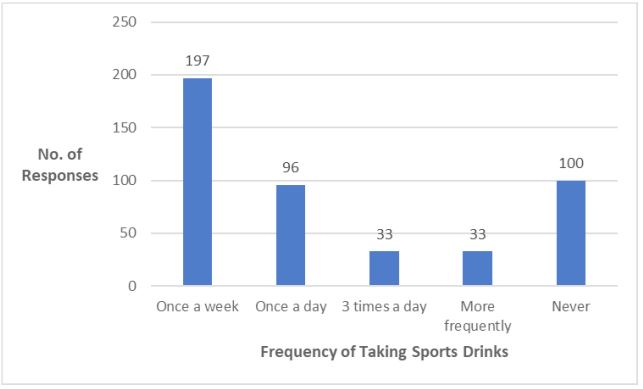

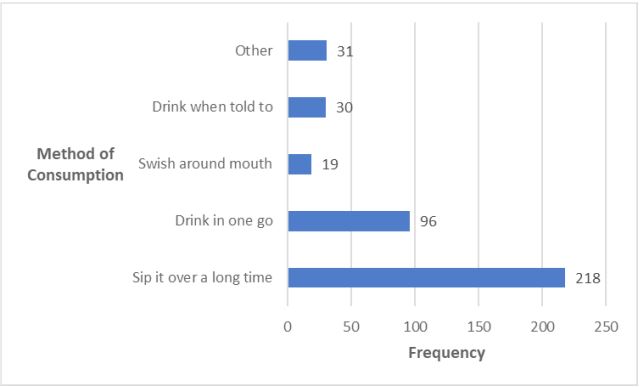

Results: 458 completed questionnaires were distributed and received. The link between the frequency of sports drinks consumption and dental decay/pain was marginally statistically significant, (X2 , p=0.077). Isotonic sports drinks and sensitivity was statistically significant (X2 , p=<0.001). 197(43%) athletes reported drinking sports drinks at least once a week; 33 athletes (7%) reported consuming sports drinks a minimum of three times a day. n=175 (35%) athletes reported that they saw their nutritionist for advice about sports drinks, only n=21 (4%) sought advice from the dentist. One in four athletes reported seeing their dentist due to pain (n=116; 25.3%).

Conclusion: This study covered a diverse group of elite athletes. It is unclear whether the use of sports drinks does result in more tooth decay, but dentists should educate athletes and their supporting teams about the potential risks from these drinks thus mitigating those potential risks.

Clinical relevance: By understanding the magnitude of the challenge of dental decay facilitated by sports drinks, it is hoped that adequate preventative measures can be put in place. Thus, supporting the athletes towards better oral health and performance.

Keywords: Dental diseases; Prevention; Sports drinks; Athletes’ awareness.

Citation: Fine P, Haughey J. Is There a Link Between the Increased Consumption of Sports Drinks and Dental Decay?. SciBase Dent Oral Sci. 2024; 2(1): 1010.

Background

There is a high incidence of poor oral health in elite athletes, throughout the world [1], which has been shown to have a negative impact on athletic performance [2]. This can result in elite athletes missing training and events, resulting in disappointment on missing out on medals, trophies and championships [3]. Oral health can be considered an integral part of general health [4]. Recent studies have indicated a link between poor oral health and systemic diseases including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, lung diseases, and obstetric complications. Periodontal diseases could therefore have serious systemic effects through blood-borne dissemination of pathogenic bacteria and through the negative impact of the inflammatory process [5]. These potential complications are highlighted even more when it comes to elite athletes, who try to ensure their whole body is in ‘perfect’ order approaching a competition [6]. The need for hydration with athletes during training and sporting events has been well established [7,8]. The consumption of sports drinks has escalated since the 1970’s and particularly since the popularisation of road running [9]. There is also a misconception that sports drinks and energy drinks are one of the same things and can be used to the same effect. Sports drinks are used to replenish electrolytes during and after strenuous exercise and contain glucose, high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose, or contain low calorie sweeteners [10]. Energy drinks contain large amounts of caffeine, added sugars, other additives, and legal stimulants such as guarana [10]. The perception is that adolescents consume sports drinks as a substitute for soft drinks as well as during exercise, whilst at home and as a healthy alternative to other drinks with a high sugar content [11] increasing the risk of dental decay the most common disease of industrialised countries [11-13]. The link between the oral microbiome and dental caries has been well established [14] as has the link between the acidity of drinks and dental erosion [15]. Very little evidence is available that shows that cow’s milk, which has a neutral pH, is an efficient recovery drink [16,17] and even less marketing of milk as a recovery drink takes place [18]. Elite athletes continually strive to attain peak physical conditioning to aid their performance [19]. Part of this process is to carefully regulate their diets, including the consumption of sports drinks, aimed at re-hydrating the athlete [11]. The dietary pattern designed to meet the high energy demands of elite competitive athletes may coincide with a high risk of developing dental caries [12] and tooth surface loss through erosion [18]. As well as being aware of the sugar content of sports drinks, we need to ensure that elite athletes are aware of the acidity (pH) of the drinks they are consuming both from a dental caries and dental erosion perspective [19]. Bryant et al. (2011) [17] reported that: ‘over 80% of their sample of elite athletes consumed sports drinks at least once a week during training. The pattern of consumption reported offers important insight into the actual risk for caries and erosion in the mouth. Almost half of the respondents reported the high frequency, high-risk consumption pattern of ‘little sips often, from a bottle’ for both sports drinks and water’ [20]. This mode of consumption is potentially significant as the pH of the oral cavity remains low for a prolonged period of time, and below the critical threshold of pH at 5.5, when demineralisation of dental enamel occurs, rather than having the opportunity to return to normal (pH 6.5-7) [21,22]. The provision of medical/dental facilities at major sporting events has become a routine part of bidding to hold an event. Athletes from around the globe use the medical and dental facilities at major games to get advice on injuries sustained through competition, as an opportunity to have a regular health check and with pain. Over 10,000 athletes attended the London 2012 Olympic Games, and 3220(30.6%) athletes were seen at the polyclinics [23]. Of those 3220 athletes there were 2105 medical consultations; musculoskeletal comprised the greatest number (52%), followed by dental (30%) and ophthalmic (9%). Approximately 5000 athletes attended the Commonwealth Games held in Birmingham, UK in July/August 2022. Medical and dental facilities were provided at the games for injured athletes or those presenting with illness. The dental facilities included three mobile dental units situated at Birmingham NEC (CGN), Warwick (CGW) and the Commonwealth Games village in Birmingham (CGB). In addition, specialist Sports Dentists attended the boxing, basketball, and hockey arenas to deal with field of play oro-facial injuries. Some 1058(21%) athletes were seen either by dentists based at one of the three mobile units or by sports dentists. The three mobile centres saw the majority of dental patients: CGN 37%; CGW 27% and CGB 36%. Approximately 50 athletes were treated for dental/oro-facial injuries, in athlete medical facilities at the boxing, basketball and hockey. This study aimed to investigate elite athletes’ perceptions of the drinks they consumed and the possible impact on their oral health.

Methods

This was a questionnaire-based study delivered at the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games. The opportunity to question elite athletes from around the world is a relatively rare occurrence but one that offered the opportunity to access approximately 5000 sports men and women from across 72 nations and territories. Low Level Ethics Approval was sought and granted (Approved ID Num-ber:6552/012). The bespoke questionnaire was designed specifically for the Commonwealth Games, taking into account that English may not be the first language of all athletes, but English was the language of the games. It was decided to keep the questionnaire to the specific research question as the athletes would have a limited time to complete the survey. Therefore, the questions were: i) demographic in nature; ii) about athletes’ experiences with sports drinks; and iii) looking into individual athletes’ previous dental experiences. The questionnaire was distributed at athletes’ canteens within the athletes’ villages throughout the venues of the games by volunteer dental students from Birmingham Dental School. A pilot study was completed amongst dental colleagues, which allowed some minor changes to the wording of one or two questions, for clarity. All questionnaires were distributed as a hard copies as it was decided that would be a more appropriate way of data collection, rather than having electronic devices available for questionnaire completion. All the volunteers were instructed how to approach athletes, what to say when requesting them to complete the questionnaire and how to answer likely questions from the athletes. All student volunteers were supervised by a senior member of the teaching staff at Birmingham Dental School. A participant in-formation sheet was available for athletes to read prior to completing the questionnaire and students were trained to answer questions about the questionnaire should any arise. Completed questionnaires were collected and stored on a daily basis in a secure, locked facility by the senior member of staff from Birmingham Dental School. The data from returned questionnaires was transferred onto an excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2019) and then transferred on an SPSS (IBM, SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) spreadsheet for analysis. Descriptive statistic will be presented as Means (SD), Median (IQR), Proportion (%) as appropriate. Estimates of the main effect will be presented as a Proportion (95% CI), predictor/confounding variables will be evaluated by Χ2 test, t-test, Mann-Whitney U test and Multiple Logistic Regression as necessary. Intra-class correlation were used to assess the reliability of the main outcome. We used the STROBE cross sectional checklist when writing our report [24,25]. Athletes from countries in the Commonwealth were invited to participate in the study when they arrived at the athlete canteen by being asked to read the Participant Information Sheet and thereby consent to complete the questionnaire. Athletes did not have any input into the design, delivery or recruitment for the study. This study was undertaken to be fully inclusive of all athletes who attended the Commonwealth Games in August 2022. Athletes were given the choice whether to take part in the study and no penalty was applied to any athlete who did not wish to take part. All students who helped with data collection were chosen at random and were volunteers. A Participant Information Sheet was given to each athlete prior to them consenting to take part in the study.

Table 1: Demographic background and sports drinks consumption.

| Frequencies | Percentage | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Countries Represented | 50 |

Britain, Canada, Australia,

New Zealand 31 Caribbean 11 South Sea Islands 21 Indian sub-continent 9 Africa 28 |

20(9.849) |

| Sports | 25 |

Individual 43 Team 27 Both 27 |

32(9.849) |

| Age | Range 16-65 | 30 | |

|

Frequency of Sports Drinks Consumed |

Never 97 Once a week 197 Once a day 96 3x a day 30 More frequently 33 |

21.4 43.5 21.2 6.6 7.3 |

90.6(60.632) |

| How do you drink |

All in one go 99 Other 31 When told to 29 Swish around 18 Sip 218 |

24.9 7.8 7.3 4.5 54.9 |

79(75.161) |

Results

A total of 458 responses were received from athletes, which represented approximately a 13% response rate of the total number of athletes attending the games. This must be seen in the context that of the 5000 athletes attending the games less than 50% would have required medical/dental treatment and so would not have come into contact with the volunteers. These athletes represented 50 countries and territories and took part in 25 different sports. The mean age of the athletes was 30 years.

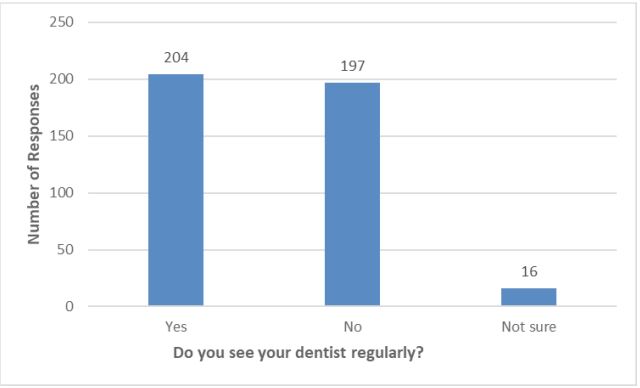

Most athletes consumed sports drinks at least once a week (n=356; 77.7%); with a few athletes admitting to consuming sports drinks >three times a day (n=33; 7.3%). Athletes from Group 1 (Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand were reported to consume sports drinks at least once a week (52.17%), whereas only 38.09% of athletes from Group 5 (Africa) consumed sports drinks once a week. Athletes who consumed sports drinks most frequently were from Group 3 (South Sea Islands), with 18.75% consuming sports drinks more than three times a day (Figure 1). The link between the frequency of sports drinks consumption and dental decay/pain appears to be marginally statistically significant (Χ2 , p=0.077). There was a highly significant relationship between the region from which the athlete came and the type of sports drink they consumed (Χ2 =<0.001). For example, 14.3% of athletes from the Indian sub-continent consumed hypotonic drinks, whether they were individual athletes (26.6% p=0.351) or part of a team event (19.7%) or both (22.3%). The largest proportion of respondents reported drinking sports drinks at least once a week (n=197; 43%). One fifth (n=95; 20.7%) of respondents reported drinking sports drinks once a day but a small minority (n=33; 7.2%) reported drinking sports drinks three times a day. However, one in twenty respondents indicated that they never drank sports drinks (n=95; 20.7%) (Figure 1).

There was no association between those athletes who constantly sip their sports drinks and dental symptoms experienced by the athletes (X2 for pain p=0.704; X2 for sensitivity p=0.272). However, there was statistical significance in relation to the consumption of Isotonic sports drinks and sensitivity (X2 , p=<0.001). Advice that had been previously given to athletes about sports drinks included that sports drinks were bad for teeth, how to consume the drink (all in one go, through a straw), that they have a high sugar content, they help re-hydration and potential harm to heart rate.

Sports drinks can be classified as Hypertonic, Hypotonic and Isotonic. Respondents to which type of drink they normally used indicated an equal spread across all three types: n=170; 37.1%; n=105; 22.9% and n=152; 33.2% respectively. 118(25.8%) of respondents did not answer this question, possibly indicating they were unsure what type of sports drink they consumed. There was no association between the type of sport the athletes were involved with (Individual, Team or Both) and the type of sports drinks they consumed. Hypertonic, (n=69, 35.9%; n=46, 40.2%; n=47, 38.8%; X2 p=0.732) hypotonic (n=51, 26.6%; n=24, 19.7%; n=27, 22.3%; X2 p=0.351) and Isotonic (n=66, 34.4%; n=32, 26.2%; n=44, 36.4%; X2 p=0.191) drinks were consumed by athletes taking part in individual or team events endurance sports or explosive sports. When asked if they were aware of the potential damaging effects of acidic sports drinks on dental enamel, 304(66%) respondents reported they were aware; 97(21%) reported not to be aware and 57(12%) stated they were not sure. There was no significance in whether athletes were participating in individual or team sports (X2 =0.732).

Figure 3 shows that most respondents seem to rely on their nutritionist for advice about the benefits of sports drinks (n=175; 35%). It is interesting to note that only n=21 (4%) of these athletes seek advice from their dentist. A significant number (n=144; 29%) of respondents reported other people advise them; these included: self-administered advice, advertising, no one and their national Olympic committee.

Approximately half of the respondents reported seeing their dentist on a regular basis (n=204, 49%). Regular in this context was defined as within the past year. 16 respondents (3.5%) were unsure when they last visited the dentist, and 41 respondents (8.5%) did not answer this question.

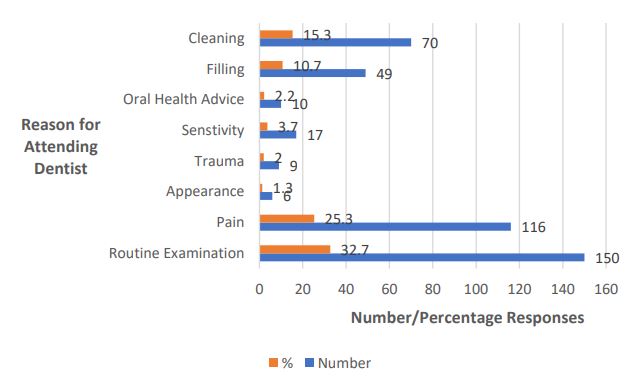

Figure 5 illustrates that one third of respondents (n=149; 35%) last visited the dentist for a routing inspection. It was interesting to note that n=116 respondents (25.3%) visited the dentist because of pain, which included pain from wisdom teeth but a relatively few number (n=9; 2%) had experienced trauma. It was also noteworthy to see that n=80 (17.5%) respondents went to have their teeth cleaned or to receive advice about their oral health. Only 10 athletes (2.2%) sought advice about their oral health status.

Discussion

The four yearly cycle of major mixed sporting events like the Olympic Games, Commonwealth Games and World Cups is an ideal opportunity to explore the dental needs of elite athletes. Approximately 5000 athletes attended the Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, UK in 2022, representing 72 counties and participating in 280 events involving 24 sports. This diversity of attending athletes was represented in the sample of athletes who completed the questionnaire and who attended the canteens within the athletic villages. Therefore, this study can be considered representative of elite athletes generally.

The primary research question for this study was to identify any link between the use of sports drinks and dental decay and/ or pain in a group of elite athletes. Of the 458 responses to the questionnaire 136(29.7%) of athletes reported attending the dentist because of pain. Khan et al. (2022) [12] reported a much higher incidence of dental pain for participants (n=83, 79.8%) related to oral or dental health. This differential could be due to the sample of athletes visited by Khan et al. were all from one country, whereas this current study reports findings from around the world, giving a truer picture of dental decay/pain with a more diverse group of athletes. Most athletes taking part in this study reported consumption of sports drinks only once a week or not at all. This was surprising and must be considered with a degree of caution as the athletes may have been aware of the possible side effects of these drinks and therefore did not want to appear to be overusing them. What was more interesting was the relatively small number of athletes who sought advice about sports drinks from a dentist (n=31, 6.8%). One third (n=167, 36.5%) relied on advice from their nutritionist and therefore saw sports drinks as part of their nutrition rather than as a possible method to rehydrate. This highlights the need for dentists to work in proximity with sports nutritionists to support the athletes [24]. This support needs to take the approach of mitigating the use of sports drinks with fluoride gels, fluoride toothpastes, regular dental inspections rather than the dentist telling the athlete not to use the sports drink. Examining the athlete on a regular basis allows the dental care provider to determine the athlete’s existing oral health, hygiene, and susceptibility to risk factors for erosion, caries, and inflammatory periodontal disease. This oral profile, in conjunction with the individual athlete’s dietary needs, can be used to establish a treatment and preventative programme, including oral health education. It was interesting to note that athletes were either not aware or not advised which type of sports drink they should use in relation to the sport they were competing in. There is ample evidence to support hypertonic, hypotonic and isotonic sports drinks used in the correct way [25]. Hypertonic sports drinks contain a higher concentration of salt and sugar than blood, making them a good way to supplement your daily carbohydrate intake or ‘top up’ glycogen stores. They also contain relatively high levels of carbohydrate, allowing athletes to refuel during some endurance events like marathons. The hypertonic drinks should be taken in combination with Isotonic drinks to replace fluid. Hypotonic sports drinks are designed to quickly replaces fluids lost through sweating. They are low in carbohydrates. They are very popular with athletes who need fluid without the boost of carbohydrate for example gymnasts. The best time to drink them is after a tough exercise work out as hypotonic drinks directly target the main cause of fatigue in sport, dehydration, by replacing water and energy fast. Isotonic drinks contain similar concentrations of salt and sugar as in the human body (5-8 grams of carbohydrate per 100 ml). They quickly replace fluids lost through sweating and supply a boost of carbohydrate. For endurance activities, such as longer bike rides these drinks quickly replace fluids and electrolytes lost through sweating and give a boost of simple carbohydrate. Awareness of potential side effects and possible sequalae of consuming sports drinks was reasonable. One third of respondents were either unaware or not sure about the potential for dental erosion caused by the acidity of sports drinks (n=155; 33.8%). This agrees with a previous study looking at students’ awareness of the ingredients and possible consequences of sport drinks, where 128(29.3%) students were unaware [26]. It was encouraging to report that 150(32.7%) of athletes visited the dentist for a routine dental inspection, but slightly more concerning that one in four (n=116; 25.3%) attended with pain. The fact that a quarter of these elite athletes suffered with dental pain before seeking advice could be due to the busy schedule the athletes work to, the reliance on pain support from their medical team, simply trying to ignore the issue by taking analgesics or ignorance about how a regular dental visit can prevent potential problems [18]. We do know that elite athletes report the negative impact that poor oral health can have on athletic performance, but they consistently don’t seek advice [1]. There is a need to educate athletes and their support teams as to the potential dangers of sports drinks and how to mitigate those dangers. Clearly elite athletes are more likely to listen to advice from their nutritionist about consuming drinks than they are to listen to their dentist. However, the fact that almost half of our athletes had not visited their dentist within the past year was a concern. This was consistent with the study by Needleman et al. (2013), who reported that 44.7% of elite athletes had not visited the dentist within the last 12 months. This relatively high figure is surprising given that these athletes prepare every part of their bodies for a major sporting event and yet their oral health is clearly neglected. This is even more surprising given the knowledge about the link between poor oral health and athletic performance [27,12,2], has been developed over the last 10 years. The limitations of this study are based around the fact that very little qualitative data was collected, and this was not considered for analysis. It would also have been an advantage to examine some of the athletes to get a true image of their dental/oral health, but facilities were not available to do any oral health screening, so the study concentrated on athletes’ perceptions of their oral health.

Clinical implications: Elite athletes need to find time within their busy schedules to have regular dental inspections and prevent dental diseases which are currently having a perceived negative impact on performance. As part of the medical team looking after these athletes’ dentists need to deliver more focused education to the athletes and their support teams.

Conclusion

This study covered a diverse group of elite athletes attending a global mixed sporting event and therefore the findings should be considered representative of elite athletes in general. It is unclear whether the use of sports drinks does result in more tooth decay but what is clear is that as sports dentists we must educate athletes and their supporting teams about the potential risks from these drinks. We have acknowledged the importance that elite athletes pay to their nutrition; what we have to do is work with the athletes and the supporting medical teams to mitigate those risks. Whilst not part of this study the use of dental screening, normally away from the competition arena, has been shown to be effective in educating athletes, preventing oral health diseases, and therefore preventing any potential risks to athletic performance [8].

Declarations

Author contributions: Conceptualization, PF and JH; methodology, PF; validation, PF and JH; formal analysis, PF; investigation PF; resources, PF and JH; data curation, PF; writing— original draft preparation, PF; writing—review and editing, PF and JH; visualization, PF and JH; project administration, PF; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional review board statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Commit-tee) of UCL Eastman Dental Institute (protocol code 6552/012 and date of approval: 16th December 2021).

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data availability statement: Data supporting these results can be obtained from the corresponding author Dr Peter Fine.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge the support given by the volunteer dental students from Birmingham Dental School, UK and from Dr Josette Camilleri and Dr Jason Niggli for their support in undertaking the study. We would also like to thank all those athletes who took the time to complete the survey and give us their valuable time.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Needleman I, Ashley P, Petrie A, Fortune F, Turner W, Jones J, Niggli J, Engebretsen L, Budgett R, Donos N, Clough T, Porter S. Oral health and impact on performance of athletes participating in the London 2012 Olympic Games: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47(16): 1054-8.

- Ashley P, Di Iorio A, Cole E, Tanday A, Needleman I. Oral health of elite athletes and association with performance: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015; 49(1): 14-19.

- Sheiham A. Sugars and Dental Decay. The Lancet1983; 321(8319): 282-284.

- World Health Organisation. The Liverpool Declaration. Promoting Oral Health in the 21st Century. 2014. http://www.who.int/oral_health/events/liverpool_declaration/en/.

- Fiorillo L. Oral Health: The First Step to Well-Being. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019; 55(10): 676.

- Needleman, Ashley, Fairbrother, Fine, Gallagher, Kings, Maughan, Melin, Naylor. 2018. Nutrition and oral health in sport: time for action. Br J Sports Med. 2018 ;52(23): 1483-1484.

- Rowlands, Kopetschny, Badenhorst. The Hydrating Effects of Hypertonic, Isotonic and Hypotonic Sports Drinks and Waters on Central Hydration During Continuous Exercise: A Systematic Meta-Analysis and Perspective. Sports Med. 2022; 52(2): 349-375.

- Maughan & Shirreffs. 2010. Dehydration and rehydration in competitive sport. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010; 20(3): 40-7.

- Cohen D. The Truth about Sports Drinks. BMJ 2012; 345. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4737.

- Khan, Qadir, Trakman, Aziz, Khattak, Nabi, Alharbi, Alshammari, Shahzad. Sports and Energy Drink Consumption, Oral Health Problems and Performance Impact among Elite Athletes. Nutrients. 2022; 14(23): 5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235089.

- Bleakley A, Jordan A, Mallya G, Hennessy M, Piotrowski JT. Do you know what your kids are drinking? Evaluation of a media campaign to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Am J Health Promot. 2018; 32(6): 1409-1416. DOI: 10.1177/0890117117721320

- Pound CM, Blair B, Boctor DL, et al. Energy and sports drinks in children and adolescents. Pediatric Child Health. 2017; 22(7): 406-410.

- Bowen WH. The Stephan Curve Revisited. Odontology. 2013; 101(1): 2-8. doi: 10.1007/s10266-012-0092-z.

- Pang, Zhi, Jian, Liu, Lin. 2022. The Oral Microbiome Impacts the Link between Sugar Consumption and Caries: A Prelimi-nary Study. Nutrients. 2022; 14(18): 3693.

- Tahmassebi & BaniHani. 2020. Impact of soft drinks to health and economy: a critical review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2020 ; 21(1): 109-117.

- Pound CM, Blair B, Boctor DL, et al. Energy and sports drinks in children and adolescents. Paediatric Child Health. 2017; 22(7): 406-410.

- Hujoel & Lingstrom. Nutrition, dental caries and periodontal disease: a narrative review. J Clinical; Periodontology. 2017; 44(S18): S79-S84.

- James, Stevenson, Rumbold, Hulston. Cow’s milk as a post-exercise recovery drink: implications for performance and health. Eurtp J Sports Science. 2019; 19(1): 40-48.

- Roy, BD. Milk: the new sports drink? A Review. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2022; 5(15): DOI: 10.1186/1550-2783-5-15.

- Bryant, McLaughlin, Morgaine, Drummond. Elite Athletes and Oral Health. Int J Sports Med. 2011; 32(9): 720-724 DOI: 10.1055/s-0031-1277192.

- Borg A, Birkhed D. Dental caries and related factors in a group of young Swedish athletes. Int J Sports Med. 1987; 3: 234-235.

- Lussi A, Jaeggi T. Erosion – diagnosis and risk factors. Clin Oral Invest. 2008;12 (suppl 1): 5-13.

- Hinds L. 2019. Sports drinks and their impact on dental health. BDJ Team. 2019; 6: 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-019-0127-1.

- Bowen WH. The Stephan Curve Revisited. Odontology. 2013; 101(1): 2-8. doi: 10.1007/s10266-012-0092-z.

- Vanhegan, Palmer-Green, Soligard, Steffen, O’Connor, Bethapudi, Budgett, Haddad, Engebretsen. 2013. The London 2012 Summer Olympic Games: an analysis of usage of the Olympic Village ‘Polyclinic’ by competing athletes. Br. J Sports Med. 2013; 47(7): 415-9.

- Broad & Rye. Do current sports nutrition guidelines conflict with good oral health? General Dentistry pages. 2015; 18-23.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. 2007. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. 2007; 335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD.

- Rowlands, Kopetschny, Badenhorst. The Hydrating Effects of Hypertonic, Isotonic and Hypotonic Sports Drinks and Waters on Central Hydration During Continuous Exercise: A Systematic Meta-Analysis and Perspective. Sports Medicine. 2022; 52: 349-375.

- Attila & Cakir. Energy-drink consumption in college students and associated factors. Nutrition. 2011; 27(3): 316-322.

- Needleman, Ashley, Fine, Haddad, Loosemore, Medici, Donos, Newton, van Someren, Moazzez, Jaques, Hunter, Khan, Shimmin, Brewer, Meehan, Mills, Porter. 2015. Oral health and elite sport performance. Br J Sport Med. 2015; 49: 3-6.