SciBase Journals

SciBase Oncology

ISSN 2996-3826

- Article Type: Research Article

- Volume 2, Issue 1

- Received: Jan 15, 2024

- Accepted: Feb 13, 2024

- Published Online: Feb 21, 2024

Living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Memories of Elderly People

Luciana Araújo dos Reis*

Department of Health I, State University of Southwest Bahia, Jequié 45.208-177, Brazil.

*Corresponding Author: Luciana Araújo dos Reis

Department of Health I, State University of Southwest Bahia, Jequié 45.208-177, Brazil.

Email: lucianauesb@yahoo.com.br

Abstract

Objective: To reveal the memories of elderly people about living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

Methods: Cross-sectional study, with a descriptive analytical character, a qualitative approach and theoretical-methodological support for the Theory of Collective Memory and the Theory of Social Representations. Carried out with 38 seniors. A questionnaire was used with sociodemographic data, health conditions and a script for a semi-structured interview. Data analysis took place with the support of the QRS NVivo® Software and in the light of Bardin’s Content Analysis.

Results: The following categories emerged: family and partner relationships and post-diagnosis sexuality. The elderly person’s memories evoke relational losses, the family social framework, recalled with feelings of abandonment, blame, the relationship extends to married life. Sexuality, maintained by the majority, with a change in behavior towards the practice of safe sex.

Conclusion: From the memories of elderly people living with the human immunodeficiency virus, the losses acquired in living with the disease are revealed, among them, the family social framework stands out, recalled with feelings of abandonment, blame that, often, makes isolation in his lonely life the only option.

Keywords: Aging; Memory; Social representations; HIV/AIDS.

Citation: dos Reis LA. Living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Memories of Elderly People. SciBase Oncol. 2024; 2(1): 1010.

Introduction

The discussion around the stigma of HIV/AIDS in old age is increasingly necessary, as there is a process of prior stigmatization of the elderly population which, added to the HIV condition, is accentuated and exerts a double burden. Fragmented assistance, which, in the vast majority of cases, does not provide comprehensive care and compromises health prevention, in addition to coping strategies adopted after diagnosis, subjects elderly people living with HIV/AIDS to situations of violence, negligence and self-neglect.

The scarcity of studies that address the daily lives of elderly people living with HIV/AIDS is notable, which reflects the existing gaps regarding collective strategies to support this group, in this aspect, however, studies at the international and national level that seek to elucidate the living and health conditions of elderly people in their experience with the virus, revealing the difficulty of acceptance and the need to modify their entire daily lives, mainly due to the prejudice and stigma surrounding the disease, issues that overlap to the physiological damage suffered by them [1].

In this scenario, a theoretical discussion around memory is required, which, in this article, constitutes the epistemological aspect and the analytical method, and which is highlighted and pioneered in the work of sociologist Maurice Halbwachs as a collective/social phenomenon. The theorist, who defends memory from its individual and collective character, considers memory as a component of the social process, since memories are the result of social interactions.

Therefore, this generation’s memories about HIV reflect on their way of coping, positions and decision-making. Knowing the memories that make up the social framework of these people, who experience the disease in their aging process, is to give a voice to these social actors, with the aim of understanding the difficulties faced, coping strategies used and, above all, promoting actions that enable the physical, social, spiritual and cultural well-being of these people, who experience helplessness in their journey with the virus. From this perspective, this article aims to reveal the memories of elderly people about living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

Materials and methods

This is an analytical-descriptive study, with a qualitative approach, based on the theory of Collective Memory and the Theory of Social Representations. This study was carried out in a Care Center for people with Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) HIV/AIDS in the interior of Bahia.

The study participants are 38 elderly people, aged 60 or over, diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, undergoing treatment at the Care Center for people with HIV/AIDS STIs, in the interior of Bahia, who were contacted/selected through collection data in clinical records and through semi-structured interviews. Thus, the following inclusion criteria were adopted: being aged 60 years or over and being registered in the reference unit.

In this sense, the exclusion criteria were: elderly people with cognitive deficits that made it impossible to participate in the research (assessed by the Mini Mental State Examination - MMSE) and elderly people who, after two attempts to contact them for the interview, were not available. After applying the MMSE, there were no patients excluded due to their cognitive capacity, however there were seven refusals: Three did not accept to participate in the research, and four made the appointment, but did not show up, even after two new contact attempts.

The data collection instruments for this study were used in two stages, on the same day of application: in the first moment, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was applied, used to exclude elderly people with cognitive deficits. And in the second moment, the application of the Script for the semi-structured interview with questions addressing: the disease and the diagnosis.

The complete MMSE consists of two sections that assess cognitive functions [6]. In the first section, orientation, memory and attention are assessed, totaling 21 points. In the second section, the ability to name, obey verbal and written commands and copy a complex drawing, in this case, a polygon, is assessed, totaling nine points. The total score is 30 points, and the cutoff point is 23/24, which is a score suggestive of cognitive deficit. In this sense, elderly people who presented a cutoff point between 23 and 24 in their results were excluded from the study.

Initially, initial contact was made with the participants to be interviewed in the waiting room, where they waited for assistance; After approval to participate, the Free Informed Consent Form (TCLE) was delivered and the signatures of the interviewees were collected. Subsequently, the collection instruments and individual interviews were applied. Data collection was carried out in a reserved room in the Care Center, from a mobile device and with the help of the KoBoToolbox software.

Based on the data collected, the recordings were fully transcribed. Then, to analyze and interpret the data collected in the interviews, Content Analysis was used, proposed by Laurence Bardin8, with the help of QSR NVivo Software version 12.

For the analysis, it was then decided to list the stages of the technique according to Bardin8, which organizes them into three phases: 1) pre-analysis, 2) exploration of the material and 3) treatment of results, inference and interpretation. Regarding QRS NVivo, it is software that allows data to be imported and stored. After creating a project in NVivo, it is possible to manage information through some responsible fields such as sources, nodes and encodings, classification and attributes. This research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of a Higher Education Institution, under opinion protocol n ͦ 3,394,696 and, after authorization, the data were collected, meeting the fundamental ethical and scientific requirements for research with human beings.

Results and discussions

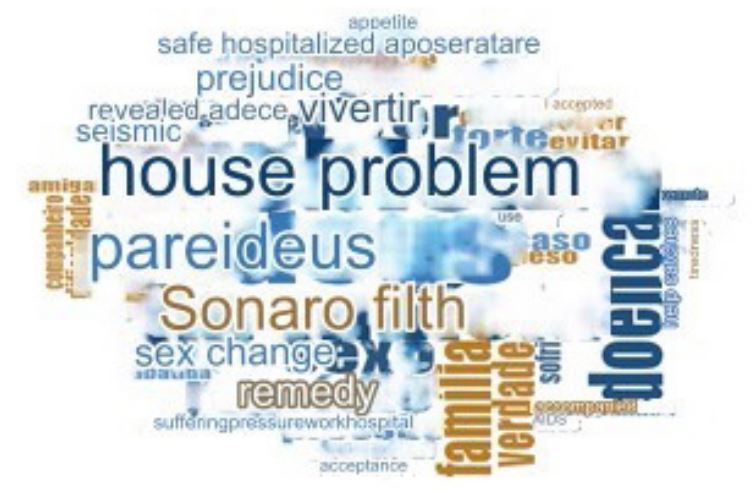

In memories about living with HIV/AIDS, the words God and problem appear at the same frequency in the narratives of elderly people, as they recall their daily lives surrounded by problems related to their diagnosis and how much they rely on their faith as psycho-spiritual support.

Followed by the words filth, disease and sex, highlighted, they talk about the place of guilt and resentment that are associated with maintaining an active affective-sexual life. The association of sexual activity with the disease materializes with the repudiation with which sex is perceived by some of those living with the virus. Then, the memory returns to life, family, prejudice, medicine, already presented in their SRs; however, from this remembrance, intimate family and partner relationships emerge, with reflections that place us at the forefront of a reality that is, to say the least, unusual, in the midst of ruptures, adjustments, mutual agreements, encounters and reunions. And, finally, the parei sentence, which emerges as a punishment, which considers sexual abstinence as a conciliation with society, in accordance with what this collective yearns for from this sexual group: the complete deprivation of affective-sexual relationships.

In view of this, the memories of living with an elderly person with HIV/AIDS, which are presented in the word cloud and in the table of the ten most evoked words, give materiality to the categories: family and partner relationships and post-diagnosis sexualities, as follows below, right after the word cloud and the table.

Category 1 relationships: Family, partner, friends

From the memories of the social relationships of the elderly person regarding their coexistence with HIV/AIDS, memories emerge of the family trajectory, of the relationships built throughout life and of the representations of family and its internal relationships in the current context. In view of this and based on Collective Memory according to [2], it is possible to infer that the memories of the past described by the elderly people in this study are full of data from the present, elaborated in the midst of the circumstances experienced, capable, even, of modifying the collective memory of this group about their relationships.

The emphasis on the social role of memory translates into concern about the perspectives of its social environment, mainly in relation to the perpetuation of moral values and traditions threatened by the diagnosis of a disease synonymous with moral transgression. The social representations of HIV/AIDS, based on the facts that occurred at the height of the pandemic, dictate the norms and rules within the family group, transmitting from generation to generation all the stigma and the conviction of the brevity of death, based on facts and marks from past.

Therefore, it is essential to understand the link between elderly people and their social network made up of family members and how much this family memory changes the course of their life with the virus. Some studies include the family as the main incentive to deal with stress and suffering resulting from serological status, acting as a protective factor and encouragement to change healthier lifestyle habits and adherence to clinical treatment [3,4].

The representations are ambiguous about family relationships, there are family members who are perceived as part of the treatment, given the importance of acceptance and solidarity, and there are conflictual relationships, which intensify negative feelings [5].

The family represents a territory for socialization and collective and individual development of its components and a source of survival strategies, regardless of the arrangement presented [6]. For the authors, the family system changes to meet the needs and transformations of society; therefore, all members of this group suffer, in some way, the impact of these internal and external changes to the group [7]. Claims that human existence has its core in group relationships, since, from birth, the individual participates in different groups, in a constant dialectic between building their individual identity and the need for group and social identity.

In this study, family relationships were ambiguous in the select group that revealed their serological status to members of their family, according to the following reports: I am well received by the doctors and everything, the family I consider is here, outside I don’t consider it family, no. When I go to my relatives’ house, there are some who don’t even come close to me. My relatives are here, the ones who don’t discriminate against me. There’s a sister who mocked me a lot, I told her to be careful, because the same way it happened to me, it could happen to anyone (Carnation 01, 66 years old, separated).

The relationship with my family has changed, yes, I have two brothers who are much closer now. They are the ones who take care of me. Friends, some are together with me and others have moved away, it was a party friendship. The only people who know are my brothers and I told just one person, who is a friend (Cravo 07, 64 years old, separated).

It’s changed a little, like, because I don’t think it’s ever the same as before. There’s always something different, it’s never the same as before. In my case, they often throw it in my face, I put up with it, I stay quiet (Carnation 14, 61 years old, stable union).

It is worth highlighting the speech of the elderly person who projects onto the multidisciplinary team their expectations of care and support for coping with the disease of family responsibility. This is a reflection of a relationship that was established in bonds and trust, not only in technical skills, but mainly in ethics, respect and a welcoming attitude invested in the care process.

Emphasize that the health services responsible for caring for people living with HIV/AIDS are care enhancers, with a major impact on the quality of life of these people, by offering holistic assistance, in which the humanistic, scientific care and the human person who lives with illness, not restricting the being, pathology and technical care. At the same time, a study carried out with elderly people living with chronic illnesses revealed that 80% of participants considered the family to be the main source of strength and reason for living, as it provides them with a feeling of belonging, comfort and security, with guaranteed physical care, psychic and moral [8].

Maintaining the domestic routine without separating daily utensils reveals this feeling of belonging; on the other hand, the report that: “it is never the same as before” highlights the ruptures in relationships, driven by blaming, often, this being the defining situation of the option for secrecy, for fear of contempt and shame for all the stigmatizing representations present in the imagination of elderly people. When living with the disease, it is necessary to incorporate numerous changes in the way of relating and in daily life activities, which concern not only the elderly person, but above all those who live with them, such as the companion. In this scenario, the relationship with the partner can become part of the therapy or be a risk factor for greater vulnerability in living with the virus. It is important to know how relationships are maintained in this territory where physical and psychological transformations occur and difficulties related to changes in sexual practices. A study that aimed to understand the life history of elderly people with HIV/AIDS, focusing on understanding the repercussions of the diagnosis on the lives of this group, revealed that elderly people perceived the existence of losses in affective relationships and in the maintenance of sexual activity [9].

In this study, there were reports of healthy maintenance of the marital relationship, however, for the majority, the relationship with the partner was affected as a result of situations of infidelity in the marital relationship, with consequent contagion with the virus and transmission to the spouse. Another frequently reported daily situation was distancing from one’s partner after the diagnosis, motivated by the fear of transmitting the disease. A third situation described was widowhood due to the death of the spouse secondary to the disease, resulting in the choice to remain alone due to the diagnosis or because age was considered an impediment to starting a new relationship. In the following excerpts, it is possible to identify some of these factors that affected the marital relationship of the elderly people in this study: I live alone. I suspect he died from this same problem. She already died. I live alone. I suspect he died from this same problem. He died about three years ago, he had the same symptoms. That’s why I think he died from this problem, he didn’t find out, because it’s very complicated in the countryside where we lived, he hadn’t even heard of HIV, he did all of them, all types of tests, but he died before even finding out. (Rosa 15, 61 years old, single). I’m alone. I live single, for fear of transmitting HIV. But people have often told me that it has nothing to do with it, just be careful, use a condom, either her or both, there’s no problem at all. But I’m worried that a condom could break and transmit HIV to other people. Now, if, by chance, I found someone else with the same problem as me, then I would accept it, understand? I think so, I’m already at that age too (Carnation 02.60 years old, single).

It’s complicated, she always passes many things on her face... betrayal and such. Right now in December he will be celebrating 40 years of marriage, through ups and downs (Cravo 03, 60 years old, married).

Memories of losses are part of relationships and living with the disease. The remembrance of the partner’s death with the same symptoms, however, without diagnosis, the inhibition of availability to form relationships, the loss of trust on the part of the spouse and even other family members, all of this outweighs the reports of a harmonious coexistence. The fact is that this phase of life is naturally made up of countless losses and can be a time of reconstruction or resignification; therefore, living with HIV/AIDS makes this experience even more exhausting [10]. Furthermore, coping with a loss for an elderly person can anticipate or intensify the experience of other losses [11]. It is noteworthy that all these losses have direct and negative implications in relation to social support and, consequently, quality of life [12], in their study with 45 elderly people, carried out in Dublin (Ireland), with the purpose of determining the level of social support perceived among elderly people living with HIV/ AIDS, found that more than 50% of the sample had low social support perception score. The lack of emotional and instrumental support as they grow older with HIV was the cry that echoed, as well as the result of a study carried out with elderly AfricanAmerican women that aimed to report their perceptions about aging with HIV [13].

It is indisputable how much the aging person needs formal and informal support at this stage of their life; however, informal support has been a prominent content, present in numerous researches about the perception of elderly people in their daily lives, in relation to support from family, friends, neighbors and religious communities, however, when it comes to people elderly women living with HIV/AIDS, there is evidence of ruptures in this informal support, so significant that they produce carelessness, isolation and abandonment [14].

The surprise at the partner’s acceptance after having his diagnosis revealed is justified with the other narratives that reveal the disappointment due to the difficulty experienced in being accepted in a relationship, or for experiencing relationships, or possible relationships falling apart after the diagnosis was confirmed. The agreed distance pact, based on waiting for the time of healing, demonstrates how negotiations occur in intimacy and how ruptures materialize and are naturalized by the elderly person, even through physical and psychologicalemotional suffering, through guilt and fear. transmission of the disease to the partner.

At the family level, the way the family reacts to the elderly person living with HIV/AIDS carries representations and meanings about the disease that are perpetuated from generation to generation through memory and are presented in positions in such a convincing way that they do not allow for questioning. or negotiations. In this way, social support, formal or informal, information and support from health professionals to the elderly person and family are capable of completely transforming the elderly person’s experience of living with HIV/AIDS.

Category 2: Post-diagnosis sexuality

The AIDS epidemic has shown, throughout its history, that there are no limits or distinctions of gender or age for the spread of HIV. Even so, the traces of the past remain vivid in the memories of certain social groups, which reaffirm the sexuality of elderly people on a daily basis as a great taboo, it seems to make no sense for society and in the social imagination, which legitimizes their asexuality, despite the epidemiological data signal the opposite, by publicizing the increase in HIV/AIDS contagion among elderly people, with transmission of sexual etiology and heterosexual relationships [15]. The authors highlight that it is urgent to overcome social representations about sexuality, such as the association with procreation, genitality, coitus, youth, marriage. The guarantee of the right to sexual health, without discrimination, with safe information and access to sexual education, must be unquestionable [16].

It is noteworthy that the construction of knowledge about sexuality and HIV/AIDS is not restricted to informational issues alone, but mainly involves understanding and the ability to assimilate the information received in this regard, after all, the elderly person must be able to deconstruct the representation about themes experienced throughout life, alive in the collective memory of this age group.

In this way, discussions that problematize in an expanded way the issues involving the sexuality of elderly people and their coexistence with HIV/AIDS, such as dialogue with a partner, safe sexuality with HIV-discordant couples and confronting prejudice by encouraging acceptance and Reception by families and society can be the light that needs to be lit in this dark and silent sea of misinformation that plagues elderly people with HIV/AIDS [17].

Exceptionally in this scenario of progressive increase in elderly people living with HIV/AIDS, either the sexuality of this group is silenced, which exposes them to contagion by other infections, or there is a total abdication of their sexuality due to the absolute lack of information about the possibility of a active sex life. In this regard, in the narratives of the elderly people in this study, we can observe that, after the diagnosis, some of these people are overcome by a feeling of disapproval and hostility regarding the topic, as follows:

I no longer have a sex life, after that, I became disgusted with these things. Sex is filth, because it was through sex that this filth came, if it wasn’t, I wouldn’t have it, no. I was naughty, then I don’t even want to know. Even a friend from the neighborhood who is getting married, I told her, friend, don’t get married, no, sex is filthy. God forbid, I don’t give advice to anyone to get married, don’t get married, that’s filth (Carnation 01, 66 years old, separated).

After I discovered the problem, I don’t do this to anyone. I’m in church too, serving Christ, I don’t do those things anymore, no (Carnation 09, 64 years old, separated).

Look, I. I don’t have relationships with her anymore, for fear of passing on this disease to her, which I know is not easy. I stay calm (Carnation 11, 78 years old, married).

The rejection of sexuality and sexual intercourse after the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS, as expressed in this study, for [10], concerns the updating of the castration that already existed in the social, moral and religious fields regarding the elderly person even before the your coexistence with the virus; In this moment of weakness and guilt, personal issues are remembered, such as the story of “being naughty”, or even the use of one’s own old age or illness as a justification for giving up an active sexual life.

According to [18], the elderly person, when giving up sexual intercourse, relates sex to infection with the virus because it occurred through sexual contact; therefore, renouncing sexual activity can represent a punishment or even a way of dealing with this new condition. Studies reveal that the domain of sexual activity is the most affected when evaluating the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS for reasons such as fear of losing their partner due to illness or conflicts, hurts and resentments arising from the diagnosis and the risk concrete transmission of the infection [19]. For the authors, all these issues culminate in the loss of libido, reduced frequency of sexual intercourse or the complete interruption of sexual activity.

[20], when elucidating the intimacy of the affective-sexual relationships of people living with HIV/AIDS, they emphasize that revealing the diagnosis to the partner can mean a breach of trust, a threat to health, as a result of which, many times, the person is sentenced to emotional and sexual withdrawal, for relating sex to dirt, mistakes, feelings of guilt and discomfort, as occurred in the narratives of the elderly people in this study.

Research with elderly women with HIV/AIDS brings to light the fact that elderly people living with the virus suffer from limitations that prevent them from building intimate affective relationships, due to the fact that the elderly women themselves do not allow themselves to do so, as in the report of Rosa (27), in which she states that she has chosen to abstain from sexual relations since her diagnosis [15]. It turns out that the search for pleasure appears as secondary to all the difficulties linked to intimacy. In this context, when elderly people choose to eliminate sexual activity from their lives, they fit into the representations and perspectives of society, which aims for their asexuality.

On the other hand, another portion of this social group affirms the option of maintaining sexual relations, as they live an active sexual life, despite insecurity, decreased sexual desire and lack of knowledge about the importance of safe sex, as revealed in the highlights that follow:

Are you crazy! There are times when I even feel ashamed of my husband, he says, “Wow, why don’t you satisfy me?” I lost the will, that’s it (Rosa 04, 65 years old, married).

My tests are undetectable, so I study a lot, I see on the internet that it gives that security, especially for her too, because she takes the medicine, so I do it without protection (carnation 14, 61 years old, stable union). There are, like, some girlfriends, so I take precautions. Without warning, I don’t like it at all (Carnation 18, 67 years old, single). The elderly person, in the experience of sexuality while living with HIV/AIDS, is faced with the reality of a seroconcordant partner, in which both partners live with the reality of contagion with the virus, or serodiscordant, in which only one partner lives with the disease [19]. Corroborating what literature data about these partnerships state, Cravo (14), in his narrative, reports maintaining the practice of unprotected sexual relations, in the mistaken belief that the use of condoms for partners living with the disease is unnecessary [19].

Undetectable viral load is another parameter taken into account, it leads elderly people to opt for unsafe sex, because the reduction of the HIV virus to undetectable levels in the body interferes with the transmission chain of sexual partners [21]. In view of this content, studies are emphatic about the need for safe sexual behavior, that is, using condoms, since unprotected sexual practice exposes partners to reinfection from ART-resistant strains, contact with different strains, and increases the risk of contagion with other STIs [22]. A study that evaluated factors associated with the inconsistent use of condoms among people living with HIV/AIDS found that the prevalence of inconsistent condom use was 28.7% of the sample, corroborating the international study that brings to light non-compliance with the condom use among people living with HIV/AIDS [23].

[15], when investigating the behavior and knowledge of elderly people living with HIV about sexuality, they concluded that they are sexually active and involved in behaviors at risk of transmitting the virus. Data like these highlight the need to promote public policies that address the issue of sexuality, with professionals who are attentive to the individual needs of this age group, considering their life trajectory, access to information and services and, mainly, their beliefs, values and their memory, guiding everyday behaviors and practices.

Psychosocial support, so important and accessible free of charge in specialized assistance services provided by the Unified Health System (SUS), must be committed to meeting the concerns that plague elderly people living with HIV/AIDS. Their fears, guilt, stigmas must be treated in depth, so that it is possible to reach intimate and hitherto inaccessible questions, making the relationship between health professionals and elderly people who receive this care a light high-tech tool, with implications for their experience with the virus in the preventive, adaptive and coping aspects of the disease.

It is important to consider their collective memory, mentioned here, as a driver of positions, since these positions have individual and collective repercussions, as they impact the lives of elderly people who are living with the virus and their entire surroundings and community. Developments in the dialogue with the elderly people in this study reveal the fact that, in the intimacy of sexual relations, nine (41%) out of the twentytwo who reported an active sexual life maintain or maintained sexual activity without using a condom after the diagnosis, in justification for maintaining the behavior learned and experienced in their sexual life trajectory, or even due to the partner’s unavailability for safe sexual practice, or lack of demand from the other. Another piece of information of equal relevance concerns contagion with another STI, with this fact being linked by the elderly person themselves to unsafe sex.

These reports are shared below:

I did it without a condom, with my first husband, he always said “ah, because I don’t like using a condom” so I said: “but you have to use it”. Now, with the second one, we are taking precautions, so this is my case, now I’m with another, but this one uses a condom (Rosa 04, 65 years old, married).

In some moments, because like that, I met someone, and it happened. So much so that I don’t know if that’s what happened, that I had a problem with syphilis, I was treated and so on (Carnation 08, 66 years old, separated).

Then we get older too and you forget, it’s not that you forget, if no one looks for it, you stay normal, calm and don’t use it (Carnation 10, 68 years married).

Although the use of condoms is considered by most elderly people in this study as a tool to prevent sexual transmission and retransmission of HIV/AIDS, its use is ignored by many, in this study, by almost 50% of those who have an active sexual life, for be one of the factors that interfere with sexual satisfaction, a barrier to pleasure or even be a reason for conflicts between partnerships, as Rosa 04 reports.

In a survey that aimed to analyze the quality of life and difficulties faced by people living with HIV/AIDS, 94% of those interviewed recognized that using condoms is the best way to avoid HIV/AIDS; however, only 19.9% report using it with steady partners, and 54.95% with casual partners (Beltrão et al. 2020). These data corroborate the results of this study, in which six out of eight women would acquire HIV/AIDS in their marital relationship and in this specific group of sexually active elderly people in which they neglect or ignore safe sexual practices, with fixed or casual partnerships.

Scientific evidence demonstrates the fragility that surrounds the affective-sexual intimacy of elderly people living with HIV/ AIDS because their sexuality is a taboo, which intensifies isolation and loneliness and resistance to the use of condoms, which can be considered a causal factor of physical, psychological and social damage to the elderly person and their respective partners [24].

Genuine communication, transparency, a deep connection and bonds established between healthcare caregivers and elderly people living with HIV/AIDS can constitute, in this conflicting scenario between information and what is practiced, a state-of-the-art tool light. The combination of these resources with the effectiveness of hard technology through ART has demonstrated its potential. Attention and care must consider the human person in their holism, however, until then, the focus has been on the disease and on controlling symptoms, as studies on the subject prove.

Conclusion

From the memories of elderly people living with the human immunodeficiency virus, the losses acquired in living with the disease are revealed, among them, the family social framework draws attention, remembered with feelings of abandonment, guilt that often makes the Isolation in your solitary conviviality is the only option. This relationship extends to marital life, due to different situations, such as widowhood due to the death of a partner, or due to the choice to abstain from relationships for fear of transmitting the virus, although there are relationships that resisted the diagnosis, even if modified, with new internal rules, including sexual abstinence. This, in this case, represents for the elderly person, in their coexistence with the virus, the payment of debt for the responsibility of contagion, while, for the spouse, it seems to symbolize the punishment and justice necessary to make coexistence possible.

Sexuality, after the diagnosis, was maintained by the majority, with a change in behavior to practice safe sex, after receiving information about the disease, in their contact with the virus; However, the lack of correct information causes some elderly people to maintain sexual abstinence for fear of transmitting the virus, or to practice unsafe sex with partners who share the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS (seroconcordant), which draws attention to the importance of clear and objective communication that reaches the elderly person’s understanding and opens up possibilities for exchanging experiences with clarification of doubts, even the most intimate ones.

References

- DE FREITAS, Luana de Fátima Garcia, et al. Memories of elderly people living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. UFSM Nursing Magazine. 2020; 10: e9-e9.

- Halbwachs M. The collective memory. Translation: Beatriz Sidou. São Paulo: Centauro. 2006.

- Araldi LM, et al. Elderly people with the human immunodeficiency virus: infection, diagnosis and coexistence. REME: Revista Mineira de Enfermagem. 2016; 20(20).

- Bonnington O, et al. Changing Forms of HIV-Related Stigma along the HIV Care and Treatment Continuum in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Temporal Analysis. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017; 93(3).

- Freitas DCC V, Ferreira Jr S. Aging: Public policies hiv/aids in the elderly. Áurea Soares Barroso & Arnoldo Hoyos & Henrique Salmazo da Silva & Ivan Fortunato (org.). 2017; 195.

- Faco VMG, Melchiori LE. In: Valle, Tânia Gracy Martins do, (org). Learning and human development: assessments and interventions. [Online]. São Paulo: Cultura Acadômica Editora. 2009; 222.

- zimerman DE. Medical education groups. GROUPS. 1997; 351.

- Borges MS, et al. Social representations about religion and spirituality. Brazilian Journal of Nursing. 2015; 68(4): 609-16.

- Nascimento EKS, et al. Life history of elderly people with HIV/AIDS. Rev. infirm. UFPE. 2017; 1716-1724.

- LIMA A P R. Sexuality in the Elderly and HIV. Longeviver Magazine. 2020.

- Kreuz G, Franco MHP. Reflections on aging, problems, and care for elderly people. Revista Kairós-Gerontologia. 2017; 20(2): 117-133.

- Okonkwo NO, Larkan F, Galligan M. An assessment of the levels of perceived social support among older adults living with HIV and aids in Dublin. Springer Plus. 2016; 5(1): 1-7.

- Warren-Jeanpiere L, Heather D, Pilar H. Life begins at 60: Identifying the social support needs of African American women aging with HIV. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017; 28:389-405.

- Tavares MCA, et al. Social support for elderly people with HIV/AIDS: An integrative review. Brazilian Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology. 2019; 22(2).

- Aguiar RB, et al. Elderly people living with HIV-behavior and knowledge about sexuality: Integrative review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2020; 25: 575-584.

- Mendonça ETM, et al. Experience of sexuality and HIV/AIDS in old age. Research, Society and Development. 2020; 9(7). https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i7.4256.

- Almeida MM, Moura DS, Pessôa RMC. Sexuality in old age: a discussion about HIV/AIDS prevention measures. Revista Ciência & Saberes – UniFacema. 2017; 3(1): 407-415.

- Araujo G M, et al. Self-care of elderly people after the diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Brazilian Journal of Nursing. 2018; 71(l 2): 793-800.

- Sá, AAM, Santos, CVM. The Experience of Sexuality of People Living with HIV/AIDS. Psychology: Science and Profession. 2018; 38(4): 773-786.

- Beltrão RPL, et al. Health and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS: A narrative review of the last 15 years. Electronic Magazine Acervo Saúde. 2020; 40: 2942-2942.

- Romero J, et al. Absence of transmission from HIV-infected individuals with HAART to their heterosexual serodiscordant partners. Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology. 2015; 33(10): 666-672.

- Reis RK, Melo ES, Gir E. Factors associated with inconsistent condom use among people living with HIV/AIDS. Brazilian Journal of Nursing. 2016; 69: 47-53.

- Kilembe W, et al. Knowledge of HIV serodiscordance, transmission and prevention among couples in Durban, South Africa. PLOS ONE, edited by Alash’le G. Abimiku. 2015; 10(4).

- Jesus G J de, et al. Difficulties of living with HIV/AIDS: Barriers to quality of life. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2017; 30(3): 301-307.